Hi there! Welcome to Pharma Study Hub. Today we’re talking about pneumonia—a common lung infection that can sometimes get pretty serious. It happens when the tiny air sacs in your lungs (called alveoli) fill up with fluid or pus. That makes breathing hard and can cause symptoms like cough, fever, chest pain, and feeling really tired.

Anyone can get pneumonia, but babies, older adults, and people with weak immunity or chronic lung problems are at higher risk. In this post, we’ll explain the major causes of pneumonia—whether it’s bacteria, viruses, or even fungi, along with its different forms, including community-acquired, hospital-acquired, and aspiration pneumonia. We’ll also cover the common symptoms you should look out for.

We’ll also discuss how doctors diagnose pneumonia using tests such as chest X-rays, blood tests, and sputum cultures. In addition, you’ll find out about the available treatment options like when antibiotics or antivirals are required, and practical prevention tips like staying up to date with vaccines, maintaining good hand hygiene, and quitting smoking.

This guide is meant to give you clear, easy-to-understand info, but it’s not a replacement for medical care. If someone has severe trouble breathing, a high fever, confusion, or bluish lips, get emergency help right away.

What is Pneumonia?

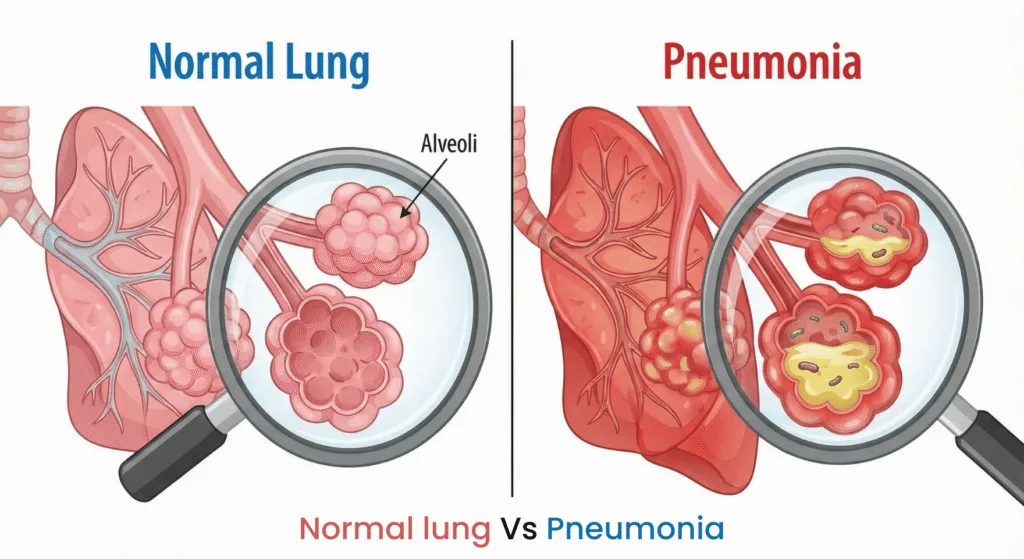

Pneumonia is a lung infection that fills tiny air sacs called alveoli with fluid or pus. Imagine the alveoli as tiny balloons filled with air from which oxygen flows into your blood—when they fill with fluid, it becomes difficult for oxygen to enter. This is why people with pneumonia often experience shortness of breath, weakness, and unusual fatigue.

Pneumonia can be caused by a variety of germs. Bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae are common causes, but viruses (like the flu or RSV) and, occasionally, fungi can also cause lung infections. How you get pneumonia and how it behaves depends on the cause: community-acquired pneumonia (occurring outside hospitals) often looks different from hospital-acquired pneumonia (which may be caused by different, sometimes more resistant, bacteria). Aspiration pneumonia also occurs, which happens when food, saliva, or vomit is inhaled into the lungs—a risk for people with swallowing problems.

In layman’s terms, pneumonia is more than just a severe chest cold. It typically causes many of the symptoms of pneumonia—a cough with or without mucus, fever, chest pain that worsens with breathing or coughing, and shortness of breath. But symptoms can vary: children may seem more irritable or unable to eat well, and adults may be confused or sleepier than usual.

Doctors often order a chest X-ray to confirm a diagnosis, as it shows areas of congestion or inflammation in the lungs. But X-rays are only one aspect of the picture—a careful medical history and physical examination, as well as other tests if needed, help determine the cause of pneumonia and the best treatment plan.

Types & Causes of Pneumonia

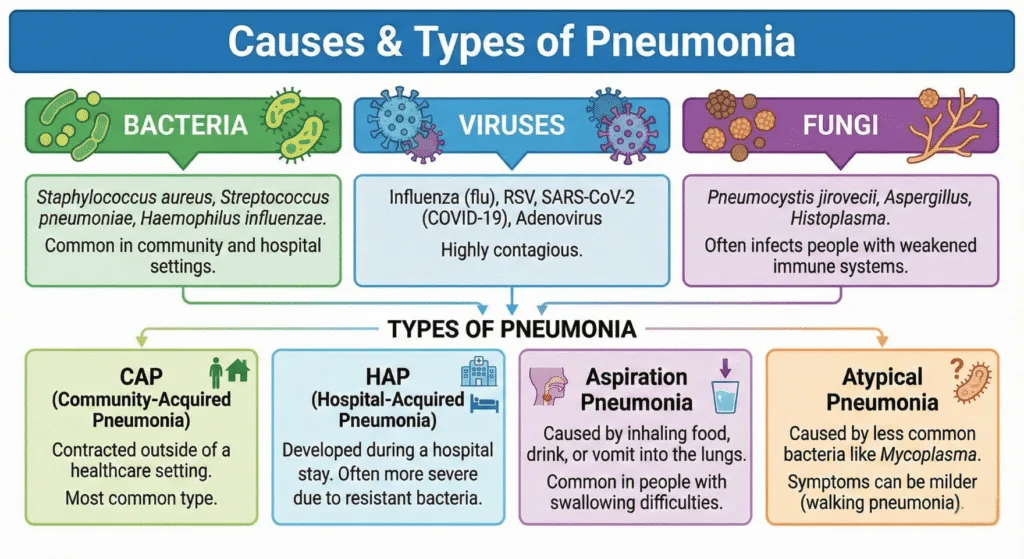

Pneumonia occurs when germs enter the lungs and cause an infection that inflames the tiny air sacs (alveoli). Causes of pneumonia fall into three broad groups: bacteria, viruses, and—less commonly—fungi.

Bacterial pneumonia is a common cause, and one of the most common bacteria is Streptococcus pneumoniae. Bacterial infections often cause a cough with mucus (sputum), fever, and a sudden, severe feeling of illness. Viral pneumonia can be caused by respiratory viruses such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), or coronavirus; viral infections sometimes begin gradually and are followed by a bacterial infection. In people with weakened immunity, some fungal pneumonias can occur, although these are rare and usually affect people with specific risk factors.

Doctors also classify pneumonia based on the condition or how the lungs are exposed to the pathogens. This guides treatment and provides clues to potential pathogens:

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) — This is pneumonia that occurs outside the hospital, in everyday life. Common causes include Streptococcus pneumoniae, unusual bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and several respiratory viruses. CAP is the type most people think of when talking about “pneumonia.”

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) — These occur when a patient is in the hospital (or on a ventilator). The bacteria involved are often different and may be more resistant to antibiotics, so the treatment approach and choice of antibiotics may vary.

Aspiration pneumonia — This occurs when food, liquids, or vomit is inhaled into the lungs, introducing bacteria from the mouth or stomach into the airways. People who have trouble swallowing or who are unconscious are at higher risk.

Atypical pneumonia — Atypical pneumonia caused by organisms such as Mycoplasma or Chlamydophila often produces mild symptoms and a different pattern on a chest X-ray, but it can still cause serious illness.

Pneumonia can also be polymicrobial, meaning more than one pathogen contributes to the infection. The type of pneumonia a person develops depends on their exposure, underlying health, and immune status — and this, in turn, affects how doctors diagnose and treat the disease.

Risk Factor

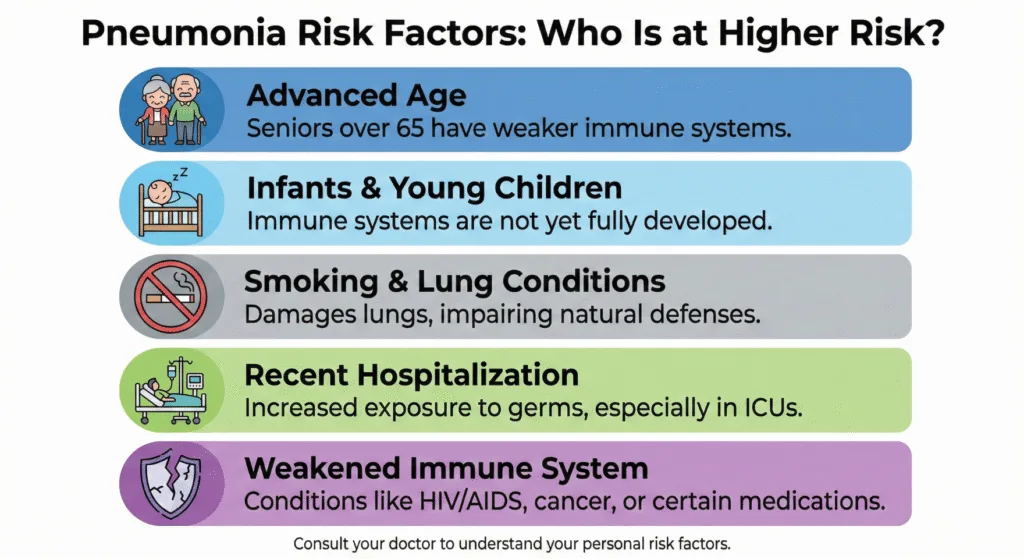

Anyone can get pneumonia, but some people are more likely to develop it or develop a severe form. Understanding the risk factors for pneumonia helps you identify who needs more attention and what measures (such as vaccination) can reduce the risk.

Common risk factors include:

- Age extremes – Infants and very young children, and older adults (especially those over 65) are at higher risk for severe pneumonia.

- Chronic lung disease – COPD, asthma, bronchiectasis, and other lung diseases make it easier for germs to thrive.

- Smoking – Damages airway defenses and greatly increases the risk of bacterial and viral pneumonia.

- Weakened immune system – From medications (steroids, cancer chemotherapy), HIV, or other conditions that weaken immunity.

- Recent hospitalization or mechanical ventilation – Increases the risk of hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated pneumonia due to different (often more resistant) bacteria.

- Swallowing problems / aspiration risk – Stroke, dementia, alcohol intoxication, or neuromuscular disorders increase the likelihood of aspiration pneumonia.

- Chronic illnesses – Heart disease, diabetes, liver or kidney disease may increase susceptibility.

- Lifestyle and social factors – Excessive alcohol consumption, malnutrition, crowded living conditions, and lack of vaccination (pneumococcal or flu vaccine) increase the risk.

Many of these factors are modifiable: Quitting smoking, getting vaccinated, managing chronic illness, and improving nutrition and oral hygiene can reduce the risk of developing pneumonia or its severe consequences.

Symptoms of Pneumonia

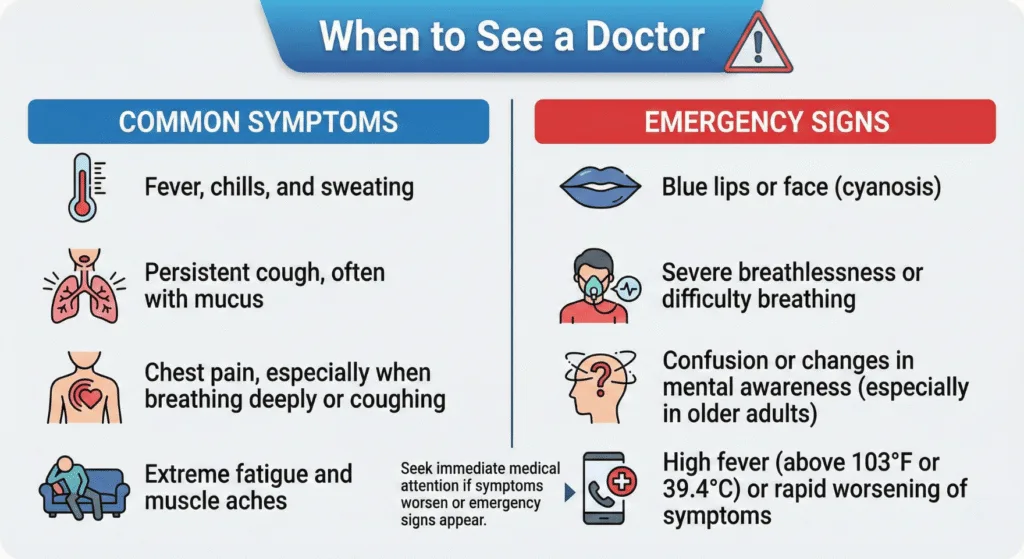

Pneumonia can present differently in each person—from a mild cough and fever to a sudden, severe illness. Knowing the common symptoms and warning signs of pneumonia helps you decide when to see a doctor or seek emergency care.

Common Symptoms

- Cough — May be dry or may produce mucus (phlegm). The mucus may be clear, yellow, green, or sometimes blood-tinged.

- Fever and chills — Often one of the first signs of infection.

- Difficulty breathing — Feeling short of breath or gasping easily with minimal activity.

- Chest pain — Usually worsened by rapid and deep breathing or coughing (pleuritic chest pain).

- Fatigue and weakness — People with pneumonia typically feel unusually tired or fatigued.

- Loss of appetite, sweating, or body aches — Common in many respiratory infections.

Symptoms may come on suddenly (especially in bacterial pneumonia) or develop gradually (often in viral or “atypical” pneumonia). The mix and intensity of symptoms depend on the cause, the person’s age, and overall health.

What the Doctor May Look for on Examination

Your doctor will examine your chest — common signs indicating pneumonia include:

- Crackles (rattling sounds)

- Decreased breath sounds in one part of the lung

- Sometimes wheezing

Vital signs may include:

- Rapid breathing rate (tachypnea)

- Rapid heartbeat (tachycardia)

- Low oxygen levels (checked with a pulse oximeter)

Atypical Symptoms

- Older adults — May not have a fever or severe cough; instead, they may become confused, unusually sleepy, or experience a sudden decline in function.

- Children — May show poor feeding, irritability, wheezing, or rapid breathing rather than typical adult symptoms.

- People with weakened immune systems — May have mild symptoms despite a serious infection, so a high index of suspicion is necessary.

Warning Signs – Seek Immediate Care

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience:

- Severe or worsening shortness of breath

- High fever that doesn’t subside

- Severe chest pain or worsening with breathing

- Confusion, fainting, or difficulty waking (especially in older adults)

- Bluish lips or face, or very pale or clammy skin

- Signs of dehydration (very little urination, dizziness)

Diagnosis of Pneumonia

Diagnosing pneumonia involves what you tell the doctor, what they hear and feel during the exam, and targeted tests. Simply put, it relies on clinical judgment, imaging, and sometimes laboratory or microbiological tests to determine the cause.

History and Physical Examination

The doctor begins by asking about:

- Symptoms — Cough, fever, shortness of breath, chest pain

- Onset — How soon they began

- Risk factors — Recent hospitalization, weakened immunity, swallowing problems

During the exam, they check your lungs for:

- Crackles (wet, crackling sounds)

- Bronchial breath sounds

- Dullness on percussion (suggests lung consolidation)

- Decreased breath sounds (possible fluid or collapse)

Chest X-ray – Common First Imaging Test

- Primary tool for confirming pneumonia

- Detects:

- Areas of consolidation (airspaces filled with fluid or pus)

- Lobar vs. patchy patterns (suggestive of bronchopneumonia)

- Pleural effusion (fluid around lungs)

Note: Early pneumonia may not show on X-rays. CT scans are used if X-rays are unclear or complications (abscess, embolus, effusion) are suspected.

Oxygen Measurement and Blood Tests

- Pulse oximetry — Checks oxygen saturation; low levels indicate severe disease

- Blood tests:

- CBC — Elevated WBC count

- CRP — Inflammation marker

- In severe cases: arterial blood gas, kidney/liver tests, blood cultures

Microbiology – Pathogen Detection

Identifying the cause guides treatment:

- Sputum Gram stain & culture

- Blood cultures (important in hospitalized patients)

- PCR & rapid antigen tests — Influenza, RSV, SARS-CoV-2, atypical bacteria

- Urine antigen tests — Pneumococcus, Legionella

- Severe cases: Bronchoscopy with lavage

Assessment of Severity – Who Needs Hospital Care?

- CURB-65 score:

- Confusion

- Urea >7 mmol/L

- Respiratory rate ≥30

- Low blood pressure

- Age ≥65

Treatment Overview

The goal of pneumonia treatment is twofold:

- Eliminate the infection (when possible)

- Support the lungs and body until recovery

What happens in practice depends on:

- Severity of illness

- Likely cause (bacterial, viral, or fungal)

- Other health problems

General Principles

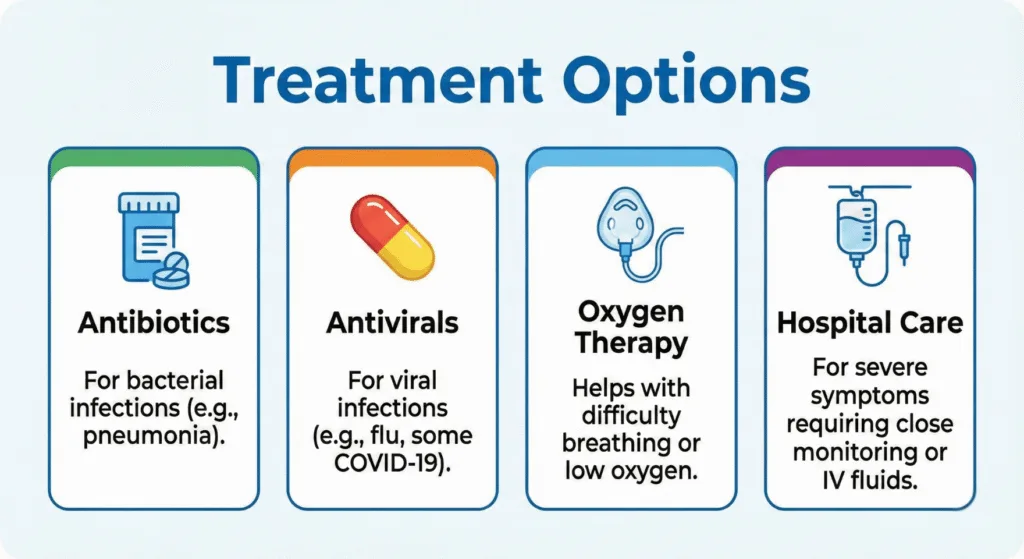

- Identify the cause — Bacterial, viral, or fungal → determines whether antibiotics, antivirals, or antifungals are needed.

- Support breathing and oxygenation — Maintaining oxygen delivery to inflamed alveoli is a priority.

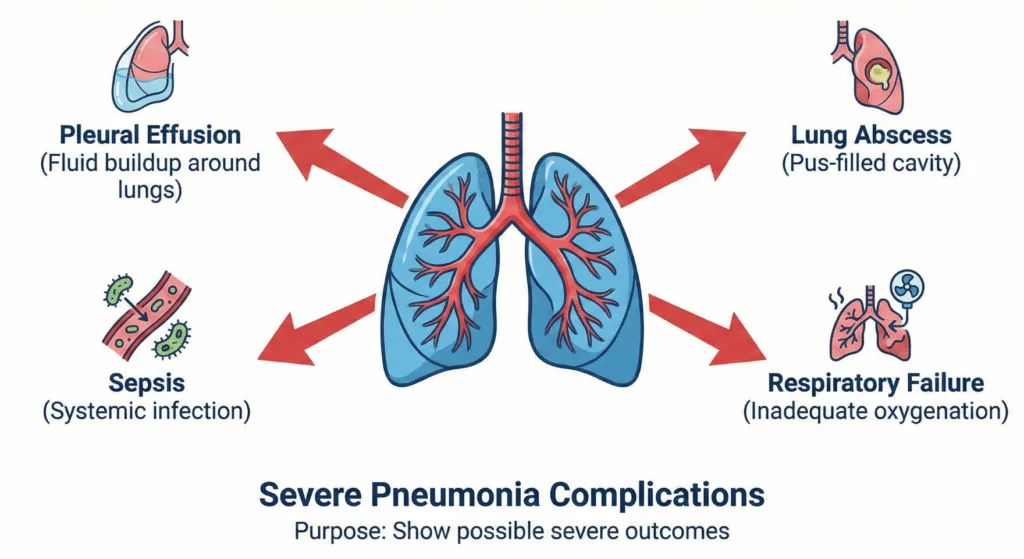

- Treat symptoms and complications — Fever, pain, dehydration, pleural effusion, or sepsis and monitor for worsening.

Outpatient vs. Inpatient Care

- Outpatient — Mild community-acquired pneumonia: oral antibiotics, rest, fluids, and close follow-up.

- Hospitalization — Recommended if:

- Low oxygen levels

- Difficulty breathing

- Unstable vital signs

- Confusion

- Other serious medical problems

- High severity score (CURB-65 or PSI)

Antibiotics (for Bacterial Pneumonia)

- Main treatment when bacterial pneumonia is suspected

- Common classes:

- Beta-lactams (penicillins, cephalosporins)

- Macrolides

- Respiratory fluoroquinolones

- Choice depends on:

- Local resistance patterns

- Patient allergies

- Community vs. hospital-acquired infection

Important: Antibiotic choice, dose, and duration must be determined by a physician. Misuse promotes resistance and harm.

Antivirals and Antifungals

- Viruses — Influenza may require oseltamivir if started early or in high-risk patients.

- Other viruses — Treatment depends on pathogen and guidelines.

- Fungal pneumonia — Rare, usually in immunocompromised patients; treated with antifungals when confirmed or suspected.

Supportive Care

- Oxygen therapy — From simple supplemental oxygen to mechanical ventilation in severe cases.

- Fluids and nutrition — Prevent dehydration and aid recovery.

- Fever and pain control — Acetaminophen or ibuprofen as directed.

- Chest physiotherapy and breathing exercises — May help mucus clearance and lung expansion.

- Monitor for complications — Pleural effusion, lung abscess, sepsis (may need drainage or ICU care).

Severe Cases and ICU Care

- Respiratory failure, very low oxygen, sepsis, multi-organ instability → Intensive care with advanced respiratory support and IV antibiotics.

Recovery and Follow-up

- Improvement within 48–72 hours of appropriate treatment

- Cough and fatigue may persist for weeks

- Follow-up — Ensure infection clears; repeat chest X-ray may be needed in older adults or smokers.

- Prevention — Vaccination (pneumococcal, flu), smoking cessation, chronic disease management.

Prevention of Pneumonia

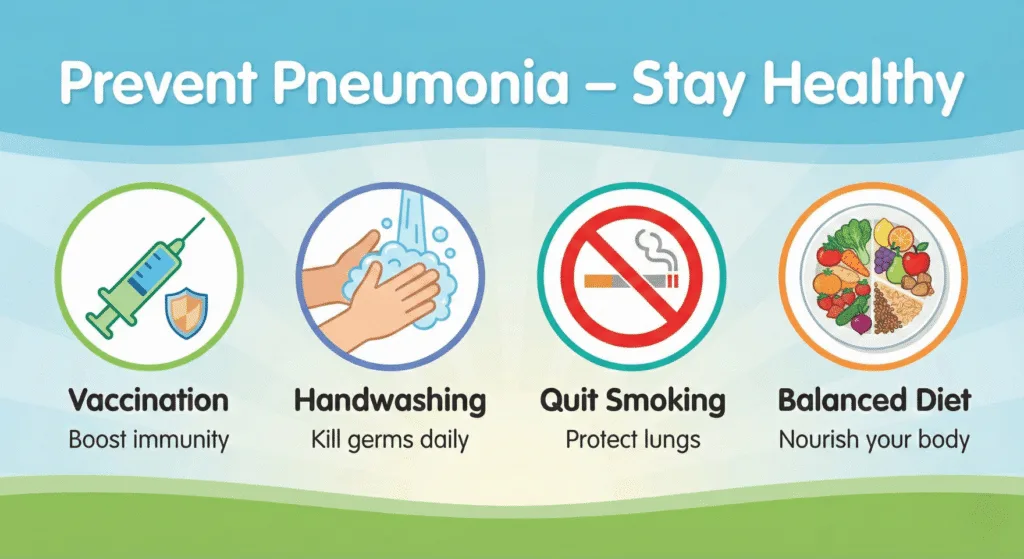

Preventing pneumonia combines everyday habits and medical measures like vaccination. Many cases—especially severe ones—can be avoided by taking steps that reduce infection risk and keep your lungs healthy.

Vaccination – One of the Most Effective Measures

- Pneumococcal vaccines — Protect against Streptococcus pneumoniae, a common bacterial cause.

Different vaccines are recommended for infants, older adults, and people with certain conditions—ask your healthcare provider which is right for you. - Seasonal influenza vaccine — Flu can cause viral pneumonia or lead to secondary bacterial pneumonia.

Annual flu shots reduce the risk of severe flu and related lung infections. - Other vaccines — Pertussis (whooping cough), COVID-19, and others may reduce severe respiratory illness depending on age and health status.

Everyday Habits That Reduce Risk

- Good hand hygiene — Wash hands with soap or use alcohol-based sanitizer.

- Cover your mouth when coughing/sneezing and avoid close contact with sick people.

- Quit smoking — Tobacco damages lung defenses and greatly increases pneumonia risk.

- Manage chronic illnesses — Control diabetes, COPD, and heart disease to lower infection risk.

- Maintain good nutrition and exercise — Supports a strong immune system.

- Oral hygiene — Regular dental care reduces bacteria inhaled into lungs, especially for older adults or those with swallowing issues.

Reduce Aspiration Risk

For those at risk (difficulty swallowing, decreased consciousness):

- Supervised feeding

- Modified food textures

- Speech/swallowing therapy

- Proper positioning during meals

Infection Control in Healthcare Facilities

Hospitals and nursing homes use:

- Strict hand hygiene

- Respiratory precautions

- Vaccination of staff and residents

- Oral care protocols

Ask about these measures if you or a loved one is hospitalized.

Practical Tips for Caregivers and Families

- Follow recommended vaccination schedules.

- Encourage high-risk individuals to get annual flu and pneumococcal vaccines.

- Seek prompt medical care if someone becomes unwell to prevent complications.

Prevention doesn’t guarantee zero risk, but vaccination + healthy habits + timely care greatly reduce the chance of severe pneumonia. If unsure about vaccines, consult your healthcare provider for personalized advice.

Pneumonia in Special Population

Pneumonia can affect anyone, but the symptoms, risks, and treatment considerations can be very different in certain groups of people. A tailored approach by a healthcare provider is essential for these special populations.

Children, especially those under the age of five, have specific considerations for pneumonia.

- Atypical Presentation: Young children may not show the classic adult symptoms like a productive cough or chest pain. Instead, caregivers should look for:

- Very rapid breathing or difficulty breathing (often the most reliable sign).

- Nasal flaring or retractions (the skin sucking in between or under the ribs during breathing).

- Poor feeding or refusal to drink.

- Lethargy, irritability, or unusual sleepiness.

- Danger Signs: Immediate medical attention is needed if a child has persistent rapid breathing, bluish color around the lips or face, or severe difficulty breathing.

- Management: Treatment often focuses on supportive care, ensuring the child is hydrated, and using antibiotics if a bacterial cause is suspected. Immunization is a critical part of prevention, following the recommended schedule for the pneumococcal vaccine and the annual flu shot.

Older Adults

Individuals over the age of 65 face a higher risk of developing pneumonia and experiencing more severe outcomes.

- Atypical Presentations: The infection often presents subtly in older adults, making it harder to spot:

- Confusion or delirium may be the only initial sign, rather than a high fever or cough.

- A sudden decline in the ability to function, such as difficulty walking or performing daily tasks.

- Low-grade fever or no fever at all.

- General weakness and fatigue.

- Higher Risk of Complications: Older adults are more likely to have underlying chronic conditions (like heart disease or COPD) that can make pneumonia much more dangerous, leading to complications like respiratory failure or sepsis.

- Vaccination and Prevention: Annual influenza vaccination and updated pneumococcal vaccines are extremely important preventive measures for this age group.

Pregnancy and Immunocompromised Individuals

These groups require a highly specialized and cautious approach to both diagnosis and treatment.

- Pregnancy: Pneumonia during pregnancy poses risks to both the mother and the fetus. Diagnosis usually relies on a chest X-ray with abdominal shielding. Treatment requires a tailored approach, as some common antibiotics are not safe during pregnancy, necessitating careful selection of medication.

- Immunocompromised Individuals: This group includes people with HIV, those undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, or those taking long-term immunosuppressant medications.

- Higher Risk: They are susceptible to a wider range of pathogens, including rare bacteria, viruses, and fungi that do not typically affect healthy people.

- Tailored Treatment: Treatment must be aggressive and often involves broad-spectrum antibiotics or specific antifungal/antiviral medications from the start. Symptoms can be very mild despite a severe underlying infection, so a high index of suspicion is always necessary.

When to Call Your Doctor

When to Contact Your Clinician

Call your doctor or make an appointment right away if you experience:

- A cold or flu that worsens instead of improving, especially if it returns with high fever or worsening cough after a few days.

- Persistent cough producing thick, colored mucus (yellow, green, or blood-tinged).

- Chest pain that feels sharp or worsens with deep breathing or coughing.

- New or worsening shortness of breath that makes daily activities difficult.

- High fever lasting more than 48 hours.

Warning Signs – Go to the Emergency Department Immediately

Do not delay. These red flags indicate severe infection and require emergency care:

- Severe difficulty breathing — Struggling to catch breath, rapid breathing, or feeling like you can’t get enough air.

- Bluish lips, face, or nail beds — Sign of dangerously low oxygen (cyanosis).

- Severe chest pain — Excruciating or unbearable pain.

- Confusion or delirium — Sudden mental changes, fainting, or difficulty waking (especially in older adults).

- Signs of sepsis — Very high or very low temperature, fast heart rate, extreme weakness or dizziness.

- Inability to drink or eat — Signs of severe dehydration (very little urination, dizziness when standing).

FAQs

Most people start to feel better within 48–72 hours of starting treatment (especially for bacterial pneumonia). However, the cough and fatigue can linger for several weeks to a few months until the lungs are fully healed.

Pneumonia itself is not contagious, but the germs that cause it are. The bacteria or virus (like the flu or RSV) that led to the pneumonia can be spread from person to person through coughing and sneezing. Good hand hygiene is key to preventing the spread

If you have bacterial pneumonia, you should typically start to see an improvement in your fever and general feeling of illness within 48 to 72 hours of starting the prescribed antibiotic. If you don’t feel better within three days, call your doctor.