Table of Contents

Introduction

“A tiny mosquito… and such a huge impact on life!“

Just think, a disease that starts with a single tiny mosquito bite sends millions of people to the hospital every year. It was once considered a disease caused by ‘bad air,’ but today, science has made it clear that malaria is a serious, life-threatening disease which can be fatal if diagnosis and treatment are delayed.

Malaria is often ignored, mistaken for a simple fever. Chills, high fever, sweating—these are the symptoms of malaria, and people often call it a viral infection and take medicines at home. But this very mistake sometimes turns into severe malaria, which is very dangerous for children, pregnant women, and those with weak immunity.

Malaria remains one of the most dangerous infectious diseases in the world today. Every year, millions of people are affected by this mosquito-borne disease. According to the World Health Organization, nearly 249 million malaria cases were reported in 2022. Of these, thousands of deaths occurred, especially among children under 5 years old in Africa.

In this blog post, we will understand in absolutely simple language:

- What are the symptoms of Malaria?

- How malaria is caused

- Its common and danger signs

- Diagnosis and treatment options

- And most importantly — prevention, so that a mosquito doesn’t control your health

Let’s learn more about this old disease and understand how modern pharmacy practice plays an important role in the fight against malaria.

What is Malaria?

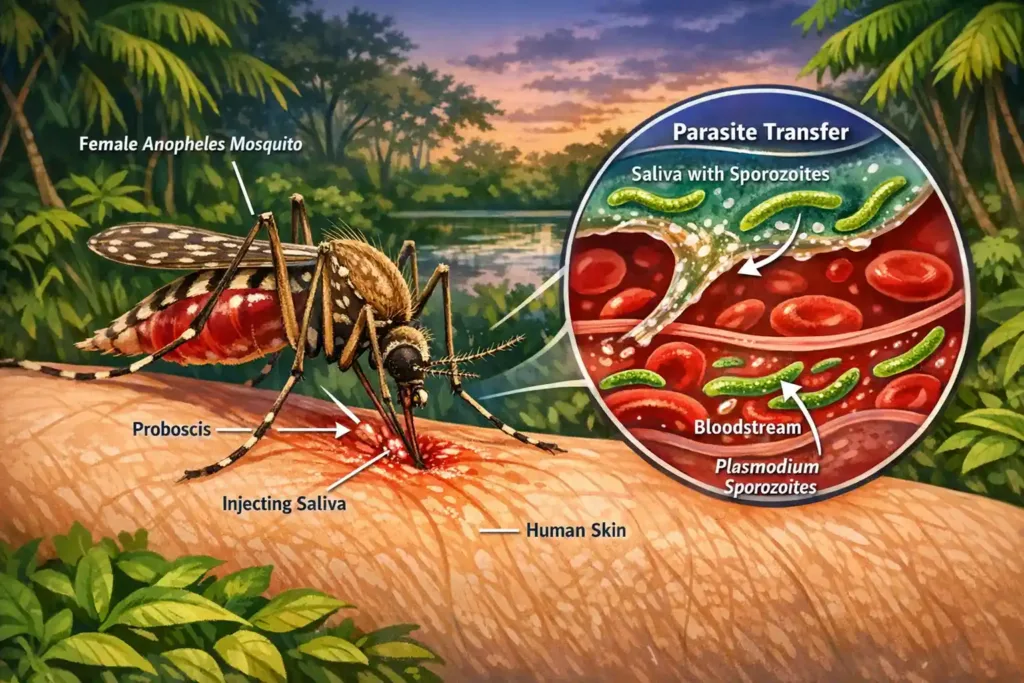

Malaria is a life-threatening infectious disease caused by a parasite called Plasmodium. This parasite is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. In simple words, when an infected mosquito bites a person, the parasite enters their body and the illness begins.

The name comes from the Italian words “mal aria,” which means “bad air,” because in old times people believed that this disease spread through bad air.

Types of Malaria Parasites

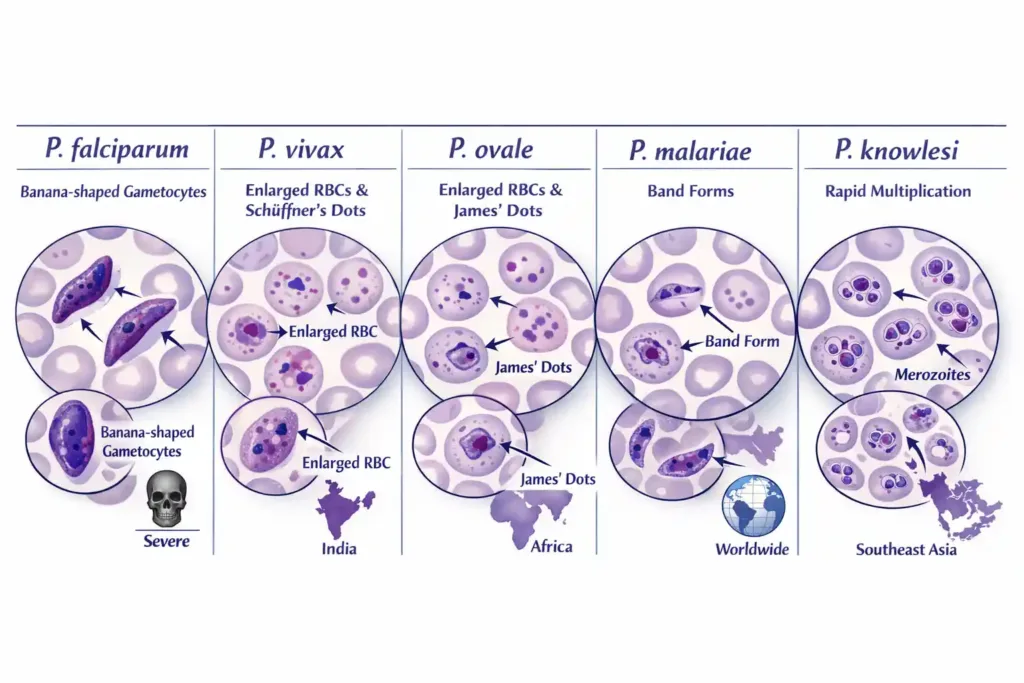

There are five main Plasmodium species that cause malaria:

- Plasmodium falciparum: This is the most dangerous type and is responsible for the maximum number of deaths. If not treated in time, it can cause severe complications like cerebral malaria and multi-organ failure. In India, this species is predominantly found in tribal and forest areas.

- Plasmodium vivax: This is the most common species in India. It is also called “benign tertian malaria.” Although it is less dangerous than falciparum, it has a distinct feature, it can remain in a dormant stage (hypnozoites) in the liver and relapse months later.

- Plasmodium ovale: This species is more common in Africa. Very few cases are found in India. Its behavior is similar to P. vivax, and it can also cause relapse.

- Plasmodium malariae: This is relatively rare, but its infection can become chronic. It is called “quartan malaria” because the fever recurs every 72 hours. It can lead to kidney problems if left untreated for a long time.

- Plasmodium knowlesi: This is primarily found in Southeast Asia and is transmitted from monkeys to humans. It multiplies rapidly and can cause severe infection.

Etiopathogenesis (Origin and Development of Disease)

Understanding how malaria occurs and how it produces disease in the body is essential for both treatment and prevention. Let’s look at it step by step.

Causative Agent (Cause)

As we read earlier, malaria is caused by parasites of the Plasmodium genus. These are single-celled organisms that fall into the protozoa category. These parasites require two hosts to survive – the mosquito (definitive host) and the human (intermediate host).

Every species has its own characteristics. P. falciparum is the most dangerous because it makes red blood cells sticky, it causes red blood cells to become adhesive, leading them to stick to the walls of blood vessels. P. vivax prefers young RBCs, while P. malariae infects mature RBCs.

Mode of Transmission (Method of Spreading)

Primary Mode – Mosquito Bite:

The main transmission of malaria occurs through the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito.

It is important to note that only the female mosquito sucks blood because it needs blood proteins to develop its eggs.

When an infected mosquito bites a healthy person, sporozoites (a form of the parasite) enter the human body with the mosquito’s saliva. This process happens in a few seconds.

The Anopheles mosquito is generally more active in the evening and at night. It breeds in stagnant water, which is why malaria cases increase during the rainy season.

Other Transmission Routes:

Besides mosquito bites, there are a few other ways, although these are rare:

- Blood Transfusion: Malaria can be transmitted if the blood of an infected person is transfused to someone else. This is why blood banks perform proper screening.

- Congenital Transmission: Malaria can be passed from a pregnant woman to her baby; this is called congenital malaria.

- Needle Sharing: Transmission is also possible among drug users who share needles.

- Organ Transplant: In very rare cases, malaria can also occur through organ transplant.

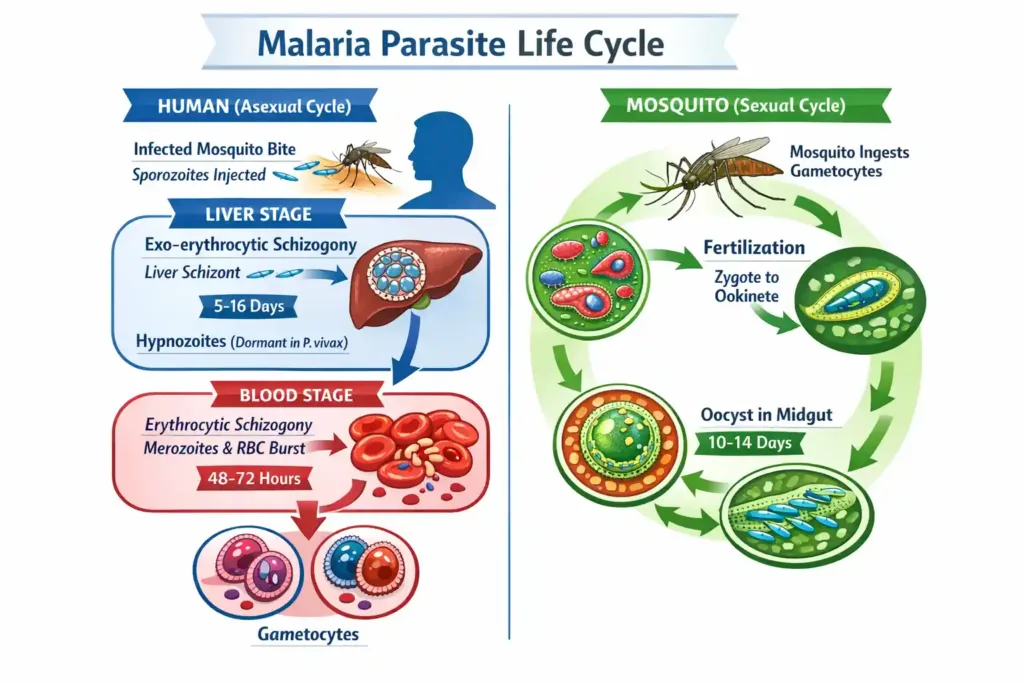

Life Cycle of Malaria Parasite

Understanding the life cycle of the malaria parasite is a bit complex but very interesting. Let’s understand it in two parts:

A. In the Human Body (Asexual Cycle):

Step 1 – Liver Stage (Exo-erythrocytic Schizogony):

When an infected mosquito bites, sporozoites enter the bloodstream.

They reach the liver cells (hepatocytes) within 30 minutes.

In the liver, they multiply and form merozoites.

In P. vivax and P. ovale, some parasites remain in a dormant form (hypnozoites) in the liver. These can activate much later and cause a relapse. This is why special drugs are needed to completely cure P. vivax.

There are no symptoms in the liver stage. This lasts for 1-2 weeks depending on the species.

Step 2 – Blood Stage (Erythrocytic Schizogony):

Merozoites are released from the liver and infect red blood cells (RBCs).

Inside the RBC, the parasite multiplies and more merozoites are formed.

When the RBC bursts, these new merozoites come out and infect other RBCs.

This cycle keeps repeating, and symptoms start in this stage. Toxins are released when the RBCs burst, which cause fever and chills.

In P. vivax and P. ovale, this cycle occurs every 48 hours (tertian pattern). In P. malariae, it’s 72 hours (quartan pattern). P. falciparum has an irregular pattern.

Step 3 – Sexual Forms:

Some merozoites turn into male and female gametocytes.

These are the sexual forms that mature inside the mosquito.

When a mosquito bites such an infected person, these gametocytes enter the mosquito.

In the Mosquito Body (Sexual Cycle):

In the mosquito’s stomach, male and female gametocytes meet and fertilization occurs.

This forms an ookinete, which penetrates the mosquito’s gut wall and becomes an oocyst.

The oocyst matures and produces thousands of sporozoites.

These sporozoites travel to the mosquito’s salivary glands.

Now, when this mosquito bites a healthy person, the cycle will start again.

Pathophysiology

RBC Destruction and Anaemia

When RBCs burst, there is a lack of healthy red blood cells in the body. This causes anaemia to develop. The patient feels weakness, fatigue, and paleness.

- In P. falciparum, infected RBCs become sticky and block small blood vessels. This prevents oxygen from reaching the organs, which can lead to serious complications.

Immune Response:

The body’s immune system detects the parasites and releases cytokines. These cytokines cause fever, chills, and inflammation. Inflammatory mediators such as TNF-alpha and interleukins increase.

Spleen and Liver Enlargement:

The spleen’s job is to remove damaged RBCs. In malaria, there are so many infected RBCs that the spleen overworks and becomes enlarged (splenomegaly). The liver can also become enlarged (hepatomegaly).

Metabolic Changes:

- Parasites consume glucose, which can lead to hypoglycaemia in the patient.

- Lactic acid build-up can cause acidosis, which is life-threatening in severe cases.

Mechanism of Complications:

- In P. falciparum, infected RBCs block the small blood vessels in the brain, causing cerebral malaria, which can lead to seizures and coma.

- Kidney failure, liver dysfunction, and pulmonary edema can also occur.

It is important to understand that malaria is not just a simple fever. It is a complex disease in which multiple body systems are affected. Therefore, timely diagnosis and proper treatment are very necessary.

Clinical Manifestations (Signs and Symptoms)

Recognizing the symptoms of malaria is very important for healthcare professionals because early diagnosis can prevent complications. Let’s see how malaria presents.

Incubation Period

The incubation period is the time between the mosquito bite and the appearance of symptoms. This time period is when the parasite multiplies in the body. The patient feels nothing during this duration.

This period depends on the parasite species:

P. falciparum: 7-14 days (average 12 days)

P. vivax: 12-17 days (sometimes up to 6-12 months if hypnozoites activate)

P. ovale: 15-18 days

P. malariae: 18-40 days

P. knowlesi: 9-12 days

Classic Symptoms

Malaria symptoms generally start suddenly and follow a very specific pattern.

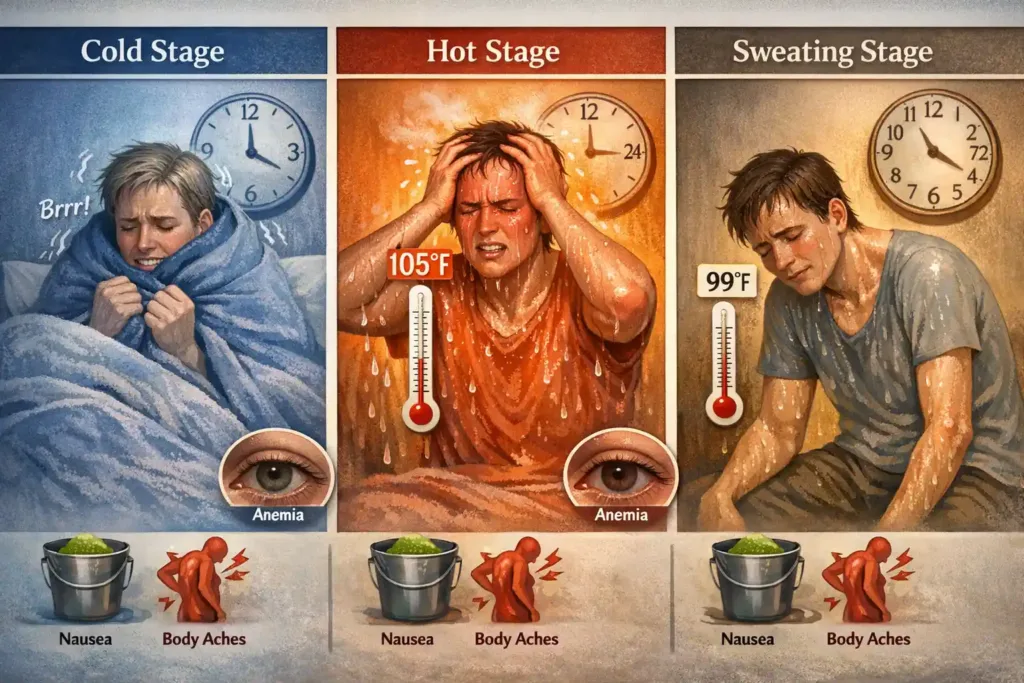

Fever Pattern:

Malaria’s most characteristic symptom is its fever pattern. This is called “malarial paroxysm,” which occurs in three stages:

Stage 1 – Cold Stage: The patient suddenly feels very cold and experiences severe shivering (rigors). Although the body temperature actually rises, the patient feels freezing and may shiver even under blankets. This stage lasts from 15 minutes to 1 hour.

Stage 2 – Hot Stage: The patient then feels very hot. The temperature can spike to 104-106°F. The skin becomes dry and hot, the face appears flushed, and the patient feels restless with a severe headache. This stage lasts 2-6 hours.

Stage 3 – Sweating Stage: Finally, the patient experiences profuse sweating, and the temperature returns to normal or sub-normal. The patient feels tired and weak and usually falls asleep afterward.

Fever Frequency:

The timing of these fever cycles depends on the species of the parasite:

In P. vivax and P. ovale: The cycle repeats every 48 hours. This is called “tertian fever” (fever comes every other day).

In P. malariae: Fever comes every 72 hours. This is called “quartan fever.”

In P. falciparum: There is no fixed pattern; the fever is irregular, and the patient may have a continuous fever.

Other Clinical Features

Chills and Rigors: Chills in malaria are very intense. The whole body shivers, and there is teeth chattering. This is completely different from a normal fever. The patient feels as if they are sitting in ice.

Headache: There is a severe frontal or generalized headache. This pain is not easily relieved even with pain medicines. The patient feels as if their head is exploding.

Body Ache (Myalgia): There is pain all over the body, especially in the back, limbs, and joints. The patient feels as if someone has severely beaten them.

Nausea and Vomiting: The patient feels like vomiting, and actual vomiting may also occur. Appetite is completely lost. Some patients also experience diarrhea.

Weakness and Fatigue: There is a feeling of extreme weakness and tiredness. The patient is unable to perform normal activities.

Physical Examination Findings

When the doctor examines the patient, some specific findings are observed:

Splenomegaly (Enlargement of the Spleen)

This is a classic finding of malaria.

The spleen becomes enlarged and can be felt in the left upper abdomen.

In chronic malaria, the spleen can be very large. Doctors check for this with palpation.

Hepatomegaly (Enlargement of the Liver)

The liver may also become enlarged, but this is less common than splenomegaly.

Tenderness may be present in the right upper abdomen.

Signs of Anemia

The patient’s skin and mucous membranes appear pale.

The conjunctiva (inside the eye) is pale, which indicates anemia.

The nails also become pale.

Jaundice

Some patients may develop jaundice. The eyes and skin look yellowish.

This occurs due to the destruction of red blood cells (RBCs).

Tachycardia

The heart rate increases, especially during fever.

The body attempts to compensate.

Dehydration

Due to vomiting, sweating, and poor oral intake, the patient becomes dehydrated.

Skin turgor decreases and mucous membranes become dry.

Complications

If malaria is not treated in time, especially P. falciparum malaria, then serious complications can develop:

Cerebral Malaria (Malaria of the Brain)

This is the most serious complication. The patient becomes confused and behaves abnormally. Seizures (fits) can occur, and in severe cases, a coma may happen. This is a medical emergency and requires immediate treatment.

Signs include: altered consciousness, seizures, neck stiffness, abnormal posturing, and coma.

Severe Anemia

RBCs (Red Blood Cells) in the blood decrease significantly. Hemoglobin can drop below 5 g/dL.

The patient experiences breathlessness, extreme weakness, and palpitations.

A blood transfusion may be necessary.

Acute Respiratory Distress

Fluid can accumulate in the lungs (pulmonary edema).

The patient has severe difficulty breathing.

Oxygen saturation decreases.

This is a life-threatening condition.

Renal Failure (Kidney Failure)

Kidneys can fail, and urine output may decrease or stop completely.

Creatinine and urea levels in the blood increase.

Dialysis may be required.

Hypoglycemia (Low Blood Sugar)

Especially in children and pregnant women, blood sugar can become very low.

The patient may become unconscious.

This can be caused by both P. falciparum and quinine treatment.

Metabolic Acidosis

Acid accumulates in the body, which is very dangerous. The patient’s breathing pattern changes (Kussmaul breathing).

Severe Malaria Syndrome

Multiple organs begin to fail simultaneously (multi-organ failure).

Blood pressure drops (shock).

Bleeding tendencies can develop.

The mortality rate is very high.

Blackwater Fever

This is a rare but serious complication involving massive hemolysis (destruction of red blood cells).

The urine becomes dark colored (black/brown).

Kidney damage may occur.

Splenic Rupture

In very rare cases, an enlarged spleen can rupture, causing internal bleeding. This is a medical emergency.

Special Presentations

In Pregnant Women

Malaria is more severe in pregnant women. The risk of complications is high.

Miscarriage, premature delivery, low birth weight baby, and maternal death can occur.

In Children

Children quickly become severe cases.

Convulsions, severe anemia, and hypoglycemia are common.

Dehydration also progresses rapidly.

First Time Infection

People who are not from malaria-endemic areas and get malaria for the first time (like travelers) have more severe symptoms because their body does not have immunity.

Patients with Partial Immunity

People living in malaria-endemic areas develop partial immunity.

Their symptoms may be mild or sometimes they may even be asymptomatic.

However, this is risky because they may not realize they have it, and treatment gets delayed.

It is important to understand all these symptoms and complications so that we can make an early diagnosis and prevent serious complications. If anyone shows any of these symptoms, especially a fever with chills that follows a typical pattern, they should seek immediate medical help.

Diagnosis of Malaria

The correct diagnosis of malaria is the first and most important step in treatment. Incorrect diagnosis will lead to inappropriate treatment, and the patient’s condition can become serious. Let’s look at the different methods of diagnosis.

Clinical Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis is based on the doctor’s experience and the patient’s symptoms. However, this alone is not sufficient.

Suspicious Features: If the patient has intermittent fever with chills and rigors, and lives in or has recently visited a malaria-endemic area, malaria should be suspected. History is very important.

The doctor typically asks:

Where the patient lives.

Whether they have recently traveled.

Whether they have had malaria before.

Since when they have had symptoms.

During the physical examination, splenomegaly (enlarged spleen) and hepatomegaly (enlarged liver) are checked.

However, confirmation cannot be made based only on clinical symptoms because the symptoms of malaria can match those of dengue, typhoid, or other febrile illnesses. Therefore, laboratory confirmation is necessary.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Laboratory tests confirm whether the patient has malaria or not, and if so, which species.

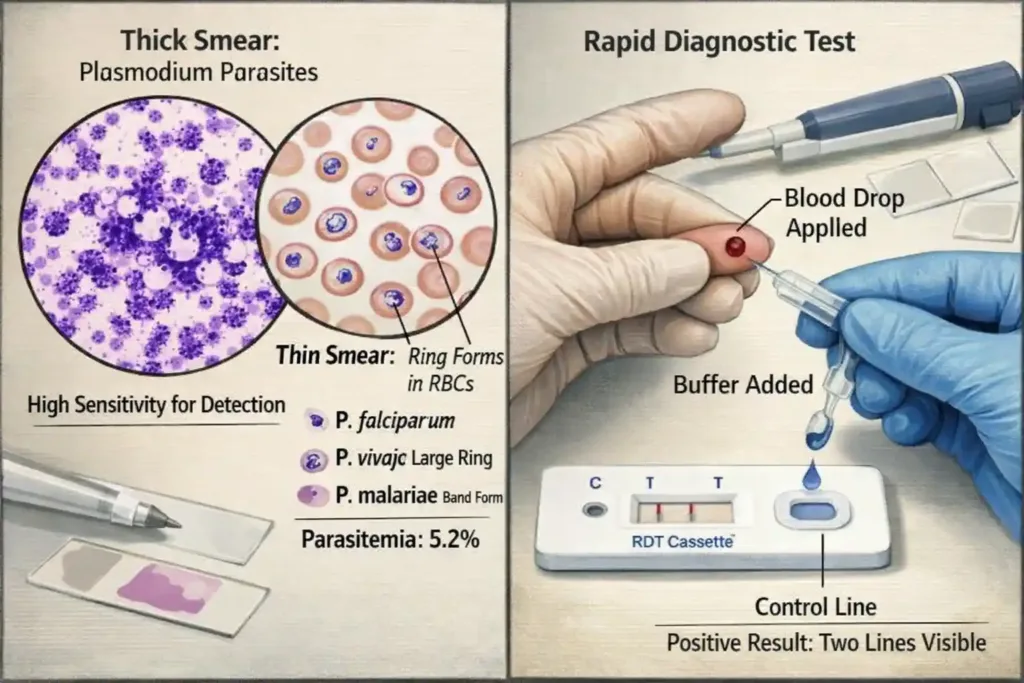

1. Microscopic Examination (Gold Standard):

This is the gold standard test for malaria diagnosis. In this, the patient’s blood sample is taken and examined under a microscope.

Thick Blood Smear:

The thick smear has a higher concentration of blood, making it easy to detect parasites.

This is best for screening.

It tells whether malaria is present or not and what the parasitemia level is (how many parasites are present).

A drop of blood is placed on a slide, stained with Giemsa stain, and viewed under a microscope.

Thin Blood Smear:

The morphology of RBCs is preserved in the thin smear, making species identification easy.

This confirms which Plasmodium species is present.

The thin smear shows the exact structure of the parasites, which is different for each species. P. falciparum ring forms, P. vivax enlarged RBCs with Schuffner’s dots, all are identified.

Parasitemia Count:

This indicates what percentage of RBCs are infected.

This assesses the severity of the disease. If parasitemia is more than 5%, it is considered severe malaria, especially in P. falciparum.

- Limitations: Microscopy requires a skilled technician. It is time-consuming (15-30 minutes). If the parasitemia is very low, a false negative result may occur. The quality of staining also affects the result.

2. Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs):

RDTs make malaria diagnosis easy and quick. These kits detect specific antigens of the parasite.

Principle: RDTs are immunochromatographic tests that detect parasite proteins. The most common antigens detected are:

HRP-2 (Histidine Rich Protein-2): P. falciparum specific

pLDH (Plasmodium Lactate Dehydrogenase): Species specific or pan-malarial

Aldolase: Pan-malarial antigen

Procedure: It is very simple.

One or two drops of blood are taken from the patient’s finger prick.

This is applied to the test kit and Buffer solution is added.

The result comes in 15-20 minutes.

The result shows a control line and a test line. The control line confirms that the test is working properly. If the test line is positive, it means the person has malaria.

Advantages: Very fast (15-20 minutes). No special training or equipment is required. Can be used in remote areas, and is Cost-effective.

Limitations: Species identification is limited. The parasitemia level is not known. In P. falciparum, HRP-2 can persist for weeks even after the infection is cleared, so a false positive may occur. Very low parasitemia is not detected.

3. Molecular Methods (PCR):

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is the most sensitive test for malaria.

Process: This detects the parasite’s DNA. A very small amount of parasite can also be detected. Mixed infections (multiple species simultaneously) are also identified.

Advantages: Very sensitive (10 times more than microscopy). Can detect low parasitemia. Species identification is accurate. Ideal for research and surveillance.

Limitations: Expensive. Requires special laboratory equipment. Trained personnel are needed. Time-consuming (several hours). Not practical for routine diagnosis.

PCR is mainly used in research settings, surveillance programs, and complicated cases.

4. Serology (Antibody Detection)

- Use: Checks for malaria antibodies.

Purpose: Does not diagnose active infection but indicates past infection. Used for blood donor screening and epidemiological surveys.

Other Supportive Tests

After malaria is confirmed, additional tests assess complications:

Complete Blood Count (CBC):

Hemoglobin: Checked to detect anemia.

Platelets: Usually low (thrombocytopenia).

WBC: Count is variable.

Liver Function Tests (LFT):

Bilirubin: May increase (indicating jaundice).

SGOT/SGPT: May be elevated, indicating liver involvement.

Renal Function Tests (RFT):

Creatinine and Urea: Checked to assess kidney function (crucial for renal failure in severe malaria).

Blood Glucose:

Checks for hypoglycemia, especially in children and pregnant women. Essential in severe malaria.

Arterial Blood Gas (ABG):

Checks for metabolic acidosis and oxygen saturation in severe cases.

Chest X-ray:

Rules out pulmonary edema if respiratory symptoms are present.

When to Test for Malaria

Definite Indications:

Anyone with a fever who is from or recently visited a malaria-endemic area.

Unexplained fever lasting more than 2-3 days.

Fever with typical symptoms (chills, rigors, sweating).

Presence of Splenomegaly or Anemia with fever.

High Risk Groups:

Pregnant women with fever (from endemic areas).

Children with unexplained fever and anemia.

Travelers returning from endemic areas with fever.

Blood donors (screening).

Diagnosis Strategy

The ideal approach is:

Clinical suspicion based on history and symptoms.

RDT for quick screening (resource-limited settings).

Microscopy for confirmation and species identification.

Assess severity by parasitemia count.

Other investigations for complications.

Non-Pharmacological Management

Malaria treatment is not limited only to giving medicines. Non-pharmacological measures are equally important for prevention, supportive care, and recovery. These measures play a very important role in controlling the disease and preventing its spread.

Prevention Strategies

Prevention is always better than cure. There are several effective strategies to prevent malaria.

A. Vector Control Measures (Mosquito Control)

The most effective way to control malaria is to control the mosquito population and prevent mosquito bites.

Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS)

IRS is a very effective method in which insecticides are sprayed on the walls of the house. When a mosquito sits on the walls, it comes into contact with the insecticide and dies.

This spraying is usually done once every 6 months. This service is provided free of cost through government programs in endemic areas. Pyrethroid-based insecticides are commonly used.

Benefits: Long-lasting protection, community-level impact, and reduction in transmission.

Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets (ITNs)

ITNs are the most popular and cost-effective prevention method. These mosquito nets are treated with insecticide that kills or repels mosquitoes.

Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs) are now available, which remain effective for 3-5 years without re-treatment. These are especially important for pregnant women and children.

Proper use is necessary: Put up the net before sleeping at night, the net should not have holes, and the net should be properly tucked so that mosquitoes cannot enter.

Larval Control

Controlling mosquito breeding is also important. The Anopheles mosquito breeds in stagnant water. Measures include:

Removing stagnant water (water containers, tires, broken pots).

Using larvicides in ponds and ditches.

Biological control such as fish (Gambusia) that eat larvae.

Improving the water drainage system.

Communities should be educated to keep their surroundings clean and prevent water collection.

Environmental Management

Mosquito breeding can also be reduced by modifying the environment:

Maintaining a proper drainage system.

Trimming bushes and vegetation (mosquitoes should not find hiding places).

Proper garbage disposal.

Avoiding water accumulation at construction sites.

Fogging and Space Spraying Fogging is done during outbreak situations or high transmission periods. This quickly kills adult mosquitoes but is a temporary solution.

B. Personal Protection Measures

Much can be done at the individual level to prevent mosquito bites.

Mosquito Repellents

DEET (N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide) based repellents are the most effective. These are applied to exposed areas of the skin. Picaridin and IR3535 are also good alternatives.

Repellent creams, lotions, or sprays can be used. It should be applied before evening time because Anopheles mosquitoes are active at night. Reapplication is required every 4-6 hours.

Natural repellents like citronella, neem oil, and eucalyptus oil are also effective to some extent but less so than synthetic repellents.

Protective Clothing Full-sleeved shirts and long pants should be worn, especially in the evening and at night. Light-colored clothes should be preferred because mosquitoes are more attracted to dark colors. Permethrin-based repellent can also be sprayed on clothes, which provides extra protection.

Other Measures

Window and Door Screens: Mesh screens should be installed on windows and doors to prevent mosquitoes from entering. The screens should not have holes.

Mosquito Coils and Vaporizers: Mosquito coils, liquid vaporizers, or electric mats can be used for indoor use. They should be used with proper ventilation.

Avoiding Outdoor Activities: As far as possible, outdoor activities should be avoided between dusk and dawn, as this is the peak biting time for Anopheles.

C. Community-Based Prevention

Awareness and collective action at the community level are very important.

Health Education: Communities should be educated about malaria—how it spreads, what the symptoms are, and how to prevent it. Awareness programs should also be conducted in schools.

Source Reduction Programs: Breeding sites can be eliminated by organizing community cleanup drives. Everyone together should keep their area clean.

Early Diagnosis and Treatment: Identifying and treating infected persons early can break the transmission chain. This is also an important part of prevention.

Supportive Care

Malaria patients require proper supportive care along with medicines, which helps in recovery.

A. Rest and Activity Modification

Complete Bed Rest:

Complete rest is essential for malaria patients, especially during the acute phase when fever and weakness are high.

Physical exertion can worsen the condition and increase the risk of complications.

Crucial: Rest is also important in cases of enlarged spleen because there is a risk of splenic rupture.

Gradual Return to Activities:

As the patient improves, activities should be resumed gradually.

Heavy work should not be done suddenly.

Full recovery may take 2-3 weeks.

B. Hydration and Fluid Management

Adequate Fluid Intake:

Dehydration is very common in malaria due to fever, sweating, vomiting, and poor oral intake.

The patient should consume 2-3 liters of fluids throughout the day (if kidney function is normal).

Recommended: Water, ORS (Oral Rehydration Solution), coconut water, fruit juices, and soups.

Avoid: Caffeinated drinks and alcohol (they increase dehydration).

IV Fluids:

Intravenous fluids are required if the patient is vomiting or unable to take fluids orally. Normal saline or Ringer’s lactate are commonly used.

Warning: Fluid overload should be avoided, especially in complicated malaria where there is a risk of pulmonary edema.

C. Nutritional Support

Balanced Diet:

Appetite is often reduced, but consuming nutritious food is essential for tissue repair and immunity.

Recommended Foods:

Protein-rich foods: Lentils, eggs, chicken, fish (for tissue repair).

Fresh fruits: Especially citrus fruits (Vitamin C for immunity).

Green leafy vegetables: Iron and folic acid (for anemia).

Whole grains: For energy.

Light, easily digestible foods.

Small Frequent Meals:

Eating too much at once is difficult. Consuming small portions 5-6 times a day is better and reduces nausea.

Avoid:

Heavy, oily, spicy foods (cause digestion problems).

Cold foods and beverages during the acute phase.

Iron Supplementation:

Recommended in the recovery phase for severe anemia.

Important: Iron is not given in the acute phase because it can promote parasite growth.

D. Fever Management (Non-Drug Methods)

Tepid Sponging:

Helpful during high fever. Sponging with normal temperature water cools the body.

Do not use ice cold water (can cause shivering).

Focus on the forehead, neck, armpits, and groin area. Repeat every 15-20 minutes.

Light Clothing:

Wear light, loose, cotton clothes that absorb sweat.

Avoid heavy blankets (unless the patient has chills).

Room Temperature:

Keep the room cool and well-ventilated.

Fans or AC can be used, but direct air should not fall on the patient.

Cold Compress:

A cold compress (wet cloth) can be placed on the forehead when the fever is high.

E. Monitoring and Observation

Vital Signs Monitoring: Check at regular intervals:

Temperature (every 4-6 hours).

Pulse rate, Blood pressure, Respiratory rate.

Oxygen saturation (if available).

Report any sudden change or deterioration immediately.

Symptoms Monitoring (Warning Signs): Watch closely for:

Increasing confusion or unconsciousness.

Severe breathlessness.

Persistent vomiting or inability to eat/drink.

Yellow discoloration of eyes (Jaundice).

Dark colored urine.

Seizures.

These signs indicate complications and require immediate medical attention.

Urine Output Monitoring:

Monitor daily urine output to assess kidney function. Decreased output can indicate renal problems.

F. Hygiene Maintenance

Personal Hygiene:

Daily sponge bath to prevent infections.

Maintain oral hygiene (brushing, mouth rinse).

Bed Hygiene:

Change bedsheets regularly, especially if sweating excessively. Clean linen prevents infections and provides comfort.

G. Psychological Support

Emotional Care:

Patients often feel anxious and depressed. Family and healthcare providers should provide emotional support and reassurance.

Maintaining a positive environment aids recovery.

Counseling:

Explain the disease, treatment duration, and expected recovery time to the patient and family to reduce anxiety.

Patient Education

Education is an important component of prevention and proper management.

A. Disease Awareness

Understanding Malaria The patient should understand what malaria is, how it spreads, and why it can be serious. Misconceptions should be cleared.

It is important to clarify that malaria is not contagious—it does not spread directly from one person to another. It only spreads through a mosquito bite.

Recognizing Symptoms The patient and family should be taught to recognize typical malaria symptoms so that early detection is possible in the future. Warning signs should also be explained.

B. When to Seek Medical Help

Patients should be given clear instructions on when to go to the hospital immediately:

High fever (>103°F) that is not controlled by medicines.

Severe headache and confusion.

Repeated vomiting.

Difficulty breathing.

Seizures.

Unconsciousness.

Dark urine or no urine.

Severe weakness.

There should be no delay in these situations.

C. Medication Compliance

Complete Course The patient should understand that it is very important to complete the full course of medicine, even if symptoms improve. Incomplete treatment can lead to recurrence and resistance.

Timing and Dosage The importance of proper timing and dosage should be explained. How to compensate for missed doses should also be explained.

Side Effects Inform about common side effects so that the patient does not panic. But also alert them about serious adverse effects that require medical attention.

D. Prevention Tips for Future

Avoiding Mosquito Bites Patients should be taught prevention measures for the future:

Using bed nets.

Applying repellents.

Wearing protective clothing.

Eliminating breeding sites.

Environmental Cleanliness The importance of keeping one’s surroundings clean should be explained. Avoid stagnant water.

Travel Precautions If traveling to an endemic area, chemoprophylaxis should be considered (with doctor’s advice).

Regular Check-ups High-risk individuals (pregnant women, children) should get regular check-ups, especially those living in endemic areas.

E. Community Responsibility

The patient should be told that they also have a responsibility to their community.

If they have malaria, they should avoid mosquito bites so that the infection does not spread to others via mosquitoes.

Participate in community programs—cleanup drives, awareness campaigns, etc.

Role of Family Members

The support of family members is very important in recovery:

Providing proper care to the patient.

Giving medicines on time.

Monitoring symptoms closely.

Providing nutritious food to aid recovery.

Giving emotional support.

Taking them to the hospital when necessary.

Implementing prevention measures at home.

Non-pharmacological management is often underestimated, but it is an integral part of the treatment. Pharmacy professionals should properly counsel the patient and family about these measures. These measures not only help in recovery but also play an important role in preventing future infections.

Medical Disclaimer

The information provided in this section, including specific drug dosages and treatment protocols, is intended solely for educational and informational purposes.

It does not constitute professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Malaria management guidelines may vary by region and are subject to change based on local drug resistance patterns and national health policies (such as the NVBDCP in India).

Readers are strongly advised to consult a qualified healthcare professional or a registered medical practitioner regarding any specific medical condition or treatment plan. Do not disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of something you have read in this blog.

Pharmacological Management

The pharmacological treatment of malaria depends on the severity of the disease, the causative species, the patient’s age, pregnancy status, and drug availability. Proper drug selection and dosing are very important for successful treatment.

Treatment Classification

Malaria treatment is divided into two categories:

Uncomplicated Malaria: Where the patient is conscious, can take oral medicines, and has no organ failure.

Severe/Complicated Malaria: Where there are serious complications, the patient is unconscious or unable to take oral medicines, or organ dysfunction is present.

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria

Uncomplicated malaria is treated with oral medicines. The treatment protocol is based on species identification.

A. Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapy (ACT)

ACT is now the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria worldwide. National guidelines in India also recommend ACT.

Why Combination Therapy?

The risk of resistance developing with a single drug is high.

Combination therapy involves two drugs that work through different mechanisms.

Artemisinin derivatives are fast-acting and quickly reduce the parasite load.

The partner drug is long-acting, eliminating the remaining parasites and preventing recrudescence.

1. Artemether + Lumefantrine (AL) This is the most commonly used ACT and is very effective, especially for P. falciparum.

Dosage (Adult):

Standard dosing: 4 tablets (each tablet contains Artemether 20mg + Lumefantrine 120mg) at 0, 8, 24, 36, 48, and 60 hours (Total 6 doses).

Pediatric Dosing (Weight based):

5-14 kg: 1 tablet per dose

15-24 kg: 2 tablets per dose

25-34 kg: 3 tablets per dose

≥35 kg: 4 tablets per dose (adult dose)

Administration:

Should be taken with fatty food (milk, biscuits, etc.) because the absorption of lumefantrine is better with fat.

Side Effects: Headache, dizziness, nausea. If vomiting occurs within 30 minutes, the dose must be repeated.

2. Artesunate + Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine (AS+SP) This is also an effective combination and is available in India.

Dosage (Adult):

Artesunate: 200mg once daily for 3 days.

Sulfadoxine (1500mg) + Pyrimethamine (75mg): Single dose on Day 1.

Contraindications:

Sulfa allergy patients.

Should be avoided in the first trimester of pregnancy.

3. Artesunate + Mefloquine

Side Effects: Mefloquine can cause neuropsychiatric side effects (anxiety, depression, hallucinations).

Contraindications: Psychiatric disorders, epilepsy, or cardiac conduction abnormalities.

4. Dihydroartemisinin + Piperaquine (DHA-PPQ)

Dosage (Adult): 3 tablets once daily for 3 days.

Advantages: Once daily dosing is convenient, long half-life, good tolerability.

B. Treatment for P. vivax Malaria

Treatment for P. vivax is in two phases:

Phase 1 – Blood Stage Treatment Blood stage parasites are cleared with ACT or Chloroquine (where sensitivity exists).

Chloroquine Dosage (Adult):

Day 1: 600mg base followed by 300mg after 6-8 hours.

Day 2: 300mg base.

Day 3: 300mg base.

Total dose: 25mg/kg over 3 days.

Phase 2 – Radical Cure (Liver Stage Treatment)

P. vivax and P. ovale form hypnozoites in the liver which cause relapse. Primaquine is necessary to eliminate them.

Primaquine Dosage (Adult): 15mg base daily for 14 days.

Important Considerations:

Primaquine can cause hemolysis, especially in patients with G6PD deficiency. Testing is recommended before starting.

Contraindicated in pregnant and lactating women.

Treatment of Severe/Complicated Malaria

Severe malaria is a medical emergency and immediate treatment is essential. These patients should be admitted to the ICU.

A. Parenteral Artesunate (First Choice)

Parenteral artesunate is the first-line treatment according to WHO and Indian guidelines.

Dosage (Adult & Child):

2.4mg/kg IV or IM at 0, 12, and 24 hours, then once daily until the patient can take oral medicines.

Minimum 3 doses are necessary even if the patient can take oral medicine early.

Preparation:

Reconstituted with 5% sodium bicarbonate, then diluted in 5% dextrose or normal saline.

Why Artesunate? Reduces mortality by up to 35% compared to Quinine.

B. Artesunate + Other Supportive Drugs

In severe malaria, complications must be managed:

Cerebral Malaria: Anticonvulsants (Diazepam) for seizures.

Severe Anemia: Blood transfusion (Packed RBCs) if Hb <5 g/dL.

Renal Failure: Dialysis if indicated. Careful fluid management.

Hypoglycemia: 50% Dextrose IV bolus followed by continuous infusion.

Metabolic Acidosis: Sodium bicarbonate (if pH <7.2).

C. Quinine (Alternative)

Used if artesunate is not available.

Side Effects: Hypoglycemia, Cinchonism (tinnitus, headache), cardiac arrhythmias.

Precautions: Cardiac monitoring and frequent blood glucose checks are essential.

Chemoprophylaxis (Preventive Medicine)

Recommended for travelers and high-risk individuals.

Doxycycline:

100mg once daily. Start 1-2 days before, continue for 4 weeks after return.

Contraindicated: Pregnancy, children <8 years.

Mefloquine:

250mg once weekly. Safe in pregnancy but watch for psychiatric side effects.

Atovaquone-Proguanil (Malarone):

Daily dose. Start 1-2 days before, continue for 7 days after return.

Chloroquine:

Only for areas with chloroquine-sensitive malaria.

Treatment in Special Populations

A. Pregnant Women Malaria in pregnancy is high-risk.

First Trimester: Quinine + Clindamycin preferred. Avoid ACTs.

Second/Third Trimester: ACT is safe. Artesunate for severe cases.

Contraindication: Primaquine is strictly prohibited.

IPTp: Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine given prophylactically in endemic areas.

B. Children

More vulnerable to severe malaria.

Artesunate is safe. Suppositories available for those who cannot swallow.

Adjunctive Therapy (Supportive Treatment)

Antipyretics: Paracetamol (500-1000mg) is preferred. Avoid Aspirin.

Antiemetics: Ondansetron or Metoclopramide to ensure oral meds are retained.

ORS: To prevent dehydration.

Monitoring & Pharmacist Role

Monitoring During Treatment

Clinical: Temperature, symptoms, vital signs.

Laboratory: Parasitemia (Days 0, 2, 3, 7, 14, 28), Hemoglobin, Glucose, Renal/Liver function.

Treatment Failure: If parasitemia is not cleared by Day 3, switch treatment.

Role of Pharmacist

Dispensing: Ensure correct drug/dosage.

Counseling: Explain complete course importance, dosing schedule, and side effects.

Adherence: Motivate patients to finish the full course.

Drug Interactions: Check for interactions (e.g., HIV meds).

National Programs (NVBDCP)

Policy:

ACT for uncomplicated P. falciparum.

Chloroquine + Primaquine for P. vivax.

Artesunate for severe malaria.

Free drugs available in government facilities.

Conclusion

Malaria is a complex but preventable and treatable disease. Success relies on early diagnosis, appropriate pharmacological intervention (such as ACT), and strict adherence to therapy to combat the growing threat of drug resistance.

However, medication alone is not enough. Non-pharmacological measures and vector control are equally vital. As healthcare professionals, our role extends beyond dispensing drugs; patient counseling and community education are powerful tools in eliminating this disease. Remember, prevention is always better than cure, and a well-informed community is the best defense against malaria.

FAQs

Malaria is caused by a protozoan parasite of the genus Plasmodium. It is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito.

The parasite primarily infects the liver (initial stage) and red blood cells (blood stage). In severe cases, it can cause dysfunction in the spleen, brain (cerebral malaria), and kidneys.

The four main species of Plasmodium that infect humans are:

Plasmodium falciparum (most severe and deadly)

Plasmodium vivax (most widespread)

Plasmodium malariae

Plasmodium ovale (Note: A fifth species, P. knowlesi, is also known to infect humans)

No, malaria is not contagious. It cannot spread directly from person to person like a cold or the flu (via coughing or sneezing). It is spread primarily by mosquito bites, though rare transmission can occur via blood transfusion, organ transplant, or from mother to child during childbirth.

Malaria transmission is highest during and immediately after the rainy (monsoon) season. This is because stagnant water creates ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes.